Inside Bharati: India’s High-Tech Research Hub in Antarctica

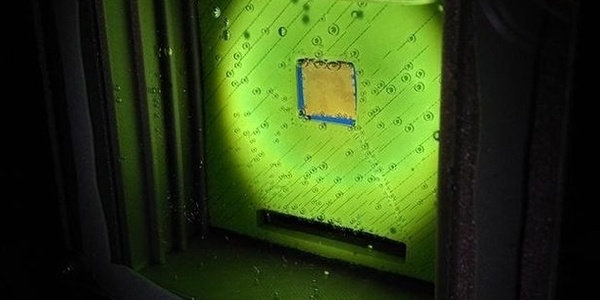

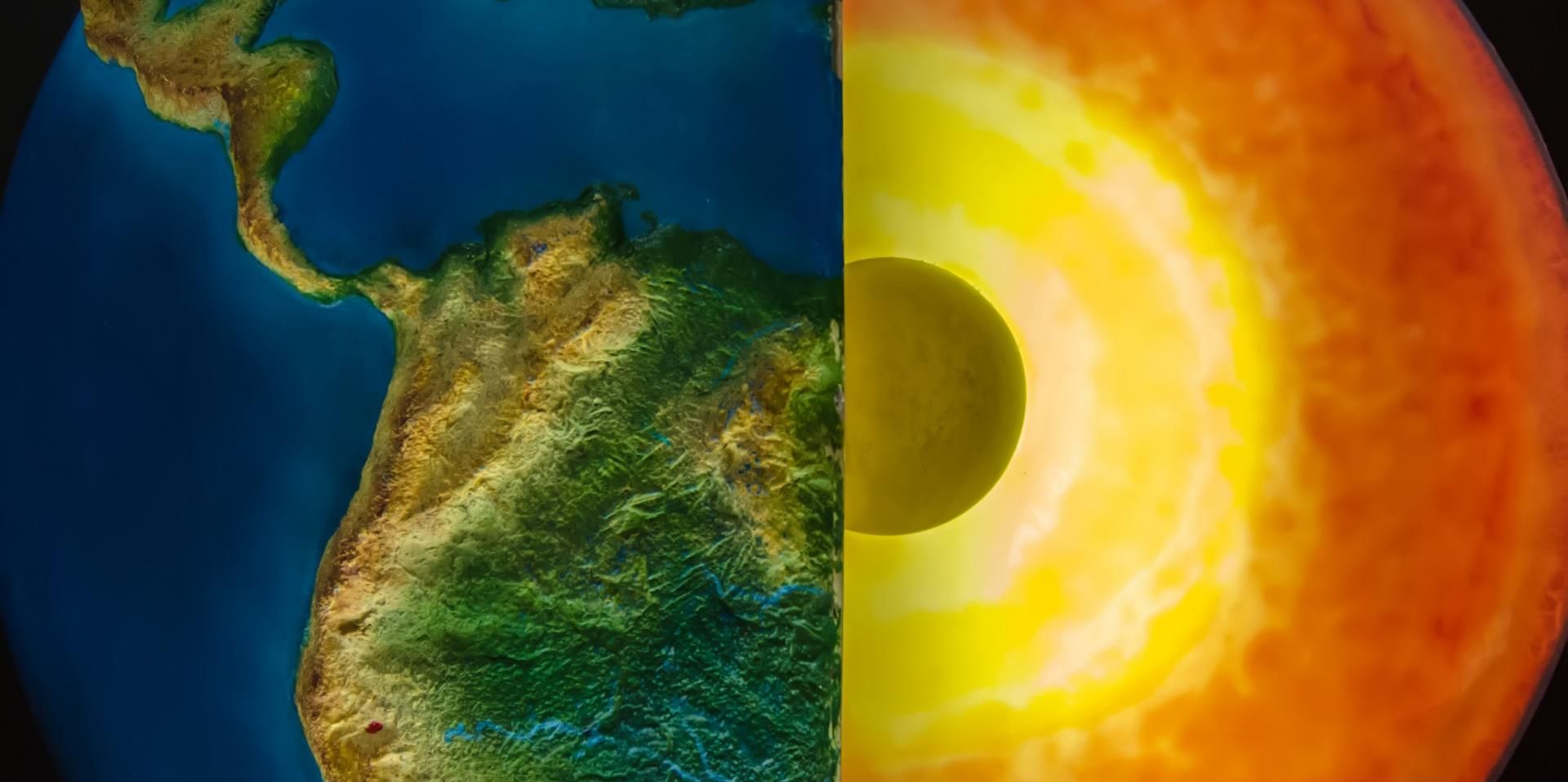

Did you know India has what looks like a futuristic spaceship in Antarctica? Standing strong amid endless ice and fierce polar winds, the Bharati Research Station is one of India’s proudest scientific achievements. Located in the remote Larsemann Hills, this permanent Antarctic research station represents not just engineering brilliance but also India’s deep commitment to global scientific exploration. Commissioned on 18 March 2012, Bharati became India’s third Antarctic research facility. Today, it operates alongside Maitri, while Dakshin Gangotri, India’s first Antarctic station, now functions primarily as a supply base. With Bharati’s completion, India joined an elite group of nations that operate multiple research stations within the Antarctic Circle.Built Like Giant Lego BlocksOne of the most fascinating aspects of Bharati is its design. The station was constructed using 134 recycled shipping containers, assembled together like giant Lego blocks. This modular approach allowed engineers to build the 2,162-square-metre facility in just 127 days—an incredible feat given Antarctica’s harsh environment. The project was undertaken by the Electronics Corporation of India Limited (ECIL) in collaboration with the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), at a contract value of ₹230 crore (approximately US$27 million). Every element of the structure was designed to withstand sub-zero temperatures, powerful winds, and heavy snowfall. Raised on stilts to prevent snow accumulation and allow wind to pass underneath, the structure minimizes environmental impact while ensuring durability. The station’s bold, colorful exterior stands out dramatically against the white Antarctic landscape, almost like a science fiction installation placed on a frozen planet.Life at -20 Degree C: Science in Extreme ConditionsLife at Bharati is not for the faint-hearted. The station can host up to 72 personnel, 47 scientists and support staff, throughout the year, and an additional 25 during the summer months. Alongside the main building, there are essential facilities such as a fuel farm, seawater pump, and summer camp shelters. Winters in Antarctica are long and isolating. Temperatures can drop well below freezing, sunlight disappears for months, and communication with the outside world becomes limited. Yet Indian scientists continue their research with determination and discipline. There is even an Indian Post Office at the station, complete with its own PIN code, MH-1718. Technically, you can send a letter to one of the coldest and most remote inhabited places on Earth. This small detail adds a human touch to an otherwise extreme scientific mission.Studying Oceans and Ancient ContinentsBharati’s primary research mandate focuses on oceanography and the study of continental breakup. Scientists here work to understand how ancient landmasses separated millions of years ago, offering clues about the geological history of the Indian subcontinent. Antarctica holds secrets about Earth’s past climate, tectonic shifts, and environmental evolution. By studying rock formations and ocean patterns in this frozen region, researchers can reconstruct how India once formed part of the supercontinent Gondwana before drifting northward. These findings do not remain confined to academic journals. They help refine climate models, improve understanding of sea-level rise, and strengthen global environmental predictions. In this sense, Bharati is not just an Indian station—it is part of a worldwide scientific effort to understand and protect the planet.A Satellite Gateway in the IceBeyond geological and oceanographic studies, Bharati also plays a crucial role in space technology. The station hosts the Antarctica Ground Station for Earth Observation Satellites (AGEOS), operated by the Indian Space Research Organisation. Through this facility, data from Indian Remote Sensing (IRS) satellites—such as CARTOSAT-2, SCATSAT-1, RESOURCESAT-2/2A, and CARTOSAT-1—is received in real time. This raw satellite data is then transmitted back to NRSC in Hyderabad for processing. The irony is beautiful: from one of the coldest and most remote places on Earth, India receives high-speed data from satellites orbiting space. Antarctica becomes a bridge between Earth and the cosmos. It truly feels like a “spaceship” stationed on ice.India’s Growing Antarctic PresenceWith Bharati and Maitri operational, India stands among nine nations that maintain multiple stations within the Antarctic Circle. This reflects India’s expanding scientific footprint and commitment to peaceful research under the Antarctic Treaty System. Antarctica is not owned by any country. It is a continent dedicated to science and cooperation. India’s presence there demonstrates its role as a responsible global scientific power, contributing to research that benefits humanity as a whole. In the silent vastness of Antarctica, beneath shifting polar skies, Bharati quietly proves that science knows no borders and neither does human determination.

(1).jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

(1).jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

(1).jpg)

.jpg)

(1).jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

(1).jpeg)

.jpg)

(1).jpeg)

.png)

.jpg)

(1).jpeg)

(1).jpeg)

(1).jpeg)

.jpg)

(1).jpeg)

(1).jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

(1).jpeg)

(1).jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

(2).jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

(1).jpeg)

.jpeg)

(1).jpeg)